The sad, strange death of Carl Hampton

The fifth-story roof of St. John Missionary Baptist Church at the intersection of Dowling and Dennis offers an unobstructed view of the neighborhood. A trained eye can easily pick out Wesley Chapel to the south, Trinity East United Methodist and Wolf’s Pawn to the west and Charles Food Store to the east. From the roof of St. John Missionary Baptist, it is difficult to miss this stretch of Third Ward’s biggest landmark, Emancipation Park.

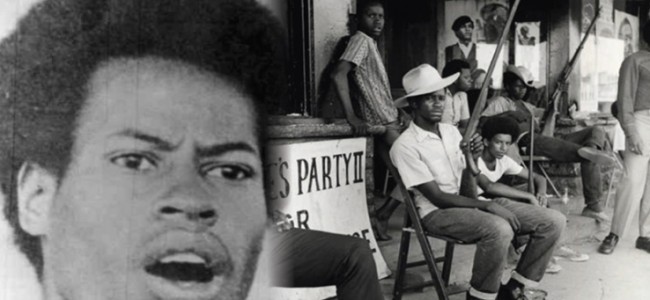

Which is why, in July 1970, two Houston Police officers picked the church’s high, flat roof for a sniper nest. The officers took position on the rooftop on July 26, 1970 in anticipation of a coming showdown between HPD and members of the Black Panther Party offshoot People’s Party II, headquartered a block away at the intersection of Dowling and Tuam.

Although media reports of the shootout would later claim that the confrontation had been building for a little over a week — since HPD officers began harassing young black men for selling The Black Panther, the official newspaper of the Black Panther Party — it had actually been building for years.

It would be an exercise in understatement to say that the late 1960s and early 1970s were a tense time between HPD and the black community. In 1967, Police Chief Herman Short’s officers pumped 3,000 rounds of shotgun and carbine ammo into a men’s dorm at Texas Southern University, the year after that outspoken black activist Lee Otis Johnson received a 30-year prison sentence for giving an undercover cop a joint.

By the time Carl Hampton came to Houston in 1969, the distrust between the community and the police had reached a fever pitch. Hampton, who had grown up in Pleasantville (east Houston) before moving to California in his teens, considered himself an urban guerilla fighter and was determined to set up a chapter of the Black Panther Party in Houston.

Unfortunately for Hampton, a previous attempt to organize a Black Panther chapter in Houston ended in disaster after accusations started surfacing that Willie “Iceman” Rudd, the chapter’s founder, was on HPD’s payroll. Although Rudd said he was an organizer for the AFL-CIO, he drove a new car and never seemed to go to work.

When Hampton tried to recruit TSU and UH students to start a chapter he got coldshouldered. Hampton ran into further problems in early 1970, when the Panther’s national office in Oakland issued a freeze on the admission of any new chapters. Undeterred, Hampton and some associates rented an office about 1.5 miles from the UH campus on Dowling.

When the People’s Party II opened shop, the area was primarily a black working class neighborhood with an open air drug market, one known for its robust trade in cough syrup. All accounts paint the first few months of the People’s Party II as fairly quiet, Hampton and his associates spent their time helping neighborhood residents recover stolen items from pawn shops and distributing food and clothing.

Things changed after two HPD officers allegedly beat Bobby Joe Conner, a young black man, to death. On April 4, 1970, HPD officers A.R. Hill and J.A. McMahon received a request for assistance from the Galena Park Police Department. The Galena Park officers were attempting to stop Conner and Taylor, another black man, for running a red light.

At the time, Conner was wanted on an auto theft warrant. According to a statement Taylor gave at the time, when the Galena Park Police officers tried to pull them over, he and Conner “panicked and ran before police caught up with them.”

Conner and Taylor fled on foot. According to his autopsy report, Conner ingested morphine while he was on the run. Galena Park Police were able to locate Conner and Taylor, arrest them and take them to a Galena Park Police station.

After the arrests, the stories begin to diverge. According to Taylor, when the HPD officers arrived, they allegedly began kicking him and Conner. Conner “fell on the floor…he was kicked when he didn’t get up. They kept telling him to get up and kept kicking him,” Taylor said at the time.

According to the theory Hill and McMahon’s attorneys presented at their trial, when the HPD officers learned that Conner and Taylor were going to be transferred to the Harris County Jail they immediately left, and Conner received his injuries from running through rubble and died from a morphine overdose.

Conner’s death created a furor in Houston’s black community. His death became a symbolic injury, his funeral a military affair. The People’s Party II served as pallbearers and provided an armed honor guard.

The Harris County District Attorney’s office was able to use the furor to get Hill and McMahon’s trial moved to relatively white town of New Braunfels.

At the 1971 trial, testimony from two additional HPD officers who responded to the call for assistance and from a Galena Park police officer, all of whom implicated Hill and McMahon in Conner’s death, failed to sway the jury who found Hill and McMahon not guilty.

While Richard “Racehorse” Haynes and Mike Ramsey, Hill and McMahon’s attorneys, spent May and June of 1970 preparing their case, the Houston black community spent the summer protesting Conner’s death. The People’s Party II organized protests in black neighborhoods like Clinton Park that attracted hundreds of people, and with the People’s Party II’s increased profile came increased attention from HPD.

It became common for HPD officers to harass People’s Party II members for selling copies of The Black Panther outside of party headquarters.

On July 17, 1970, Carl Hampton drove up to the People’s Party II headquarters and saw two white HPD officers harassing a party member for selling copies of The Black Panther on the street. Hampton was open carrying a pistol in a shoulder holster when he questioned the cops about the harassment.

Although it was legal to openly carry a pistol at the time, the HPD officers still wanted to know why Hampton had the gun. Some sources say that Hampton tried to explain the law to a recalcitrant HPD officer only to have the cop draw his gun, others say that Hampton pulled his gun first. Either way, Hampton and the two HPD officers wound up in a Mexican standoff in the middle of Dowling Street.

It’s not clear how long Hampton and the police officers stared each other down, but the tension was broken when armed members of the People’s Party II came out of their office and escorted Hampton inside.

By the time the party members entered the building, HPD officers were converging on the corner of Dowling and Tuam. Before the cops could storm the People’s Party II headquarters, hundreds of Third Ward residents, many of them armed, had surrounded the building — effectively creating a human shield for those inside.

HPD officers in riot gear arrived on the scene and began positioning themselves behind buildings and cars. In an attempt to defuse the situation, an HPD commanding officer entered the People’s Party II headquarters to try to negotiate Hampton’s surrender.

Remembering the alleged beating death of Conner, Hampton said that he had better chances on the streets with his lawyer negotiating his terms of surrender, according to Houston historian Charles “Boko” Freeman’s telling of the events.

Seeing no hope of compromise, the HPD officer left the People’s Party II headquarters. Not wanting to open fire on an entire neighborhood, HPD backed down without arresting Hampton or any members of the People’s Party II. The police department’s decision not to try to arrest Hampton only emboldened the party members.

“On several evenings after that, armed party members and their sympathizers paraded in Dowling Street, sometimes stopping traffic and asking for donations to their cause,” according to a July 28, 1970 Houston Post editorial. The party members seemed to become bolder with each passing day, and neighborhood residents and those involved in revolutionary politics could see that a showdown was coming.

Ovide Duncantell, a black activist unaffiliated with the People’s Party II, appeared at a Houston City Council meeting to warn HPD to stay away from the party headquarters.

“The law will be enforced in the 2800 block of Dowling as it is everywhere. There is no place in this city where a policeman can’t go,” HPD chief Herman Short responded, according to the Houston Chronicle.

Although tensions between the police and the party members remained high for the next few days, there were no confrontations. On July 25, Carl Hampton even gave an interview about the situation to a reporter from KULF, according to media reports at the time.

On the evening of July 26, two patrolling HPD officers saw two armed black teenagers walking in the middle of Dowling near the Tuam intersection. One of the teens pointed a weapon at the officers before running to the back of the St. John the Missionary Baptist Church, according to an HPD statement from the time.

When the 19-year-old reached the church door, he allegedly leveled his pistol at the police officers again, but the officers refrained from shooting because two “church women were immediately behind the armed youth,” according to the Houston Chronicle.

Three male members of the St. John the Missionary’s congregation were able to subdue the 19-year-old and wrestle his gun away, the Chronicle reported. Within hours of the arrest, the People’s Party II had organized a rally at Emancipation Park to raise bail money.

As word of the rally spread, more than 200 HPD officers descended on Dowling Street, and two officers from HPD’s Criminal Intelligence Division, which works to shut down organized crime and terrorist groups, took up a position on the roof of St. John the Missionary Baptist Church, allegedly to provide cover fire in case of People’s Party II snipers.

The two HPD officers on the roof of the church also allegedly brought along the reporter who had interviewed Hampton the day before, according to reports in various black newspapers. The police allegedly asked the reporter along to identify Hampton for the CID officers, according to The Burning Spear, a publication of the New Uhuru Movement.

Hampton exited the People’s Party II headquarters around 10:30 p.m. to investigate rumors of HPD officers on the roof of St. John the Missionary Baptist Church. Hampton, who was armed, snuck behind a telephone pole and peered in the direction of the church. Hampton peering from around a telephone pole is the last detail that both the black community and HPD agree on.

The official HPD record of the event describes Hampton and other members of the People’s Party II shooting at the officers on the church roof and the officers returning fire out of self-defense; it doesn’t mention the reporter as being on the roof. The accepted truth in the black community is that the reporter identified Hampton when he stuck his head around the pole and the HPD snipers, outfitted with military surplus night vision scopes for their rifles, shot Hampton.

No one may ever know whether Hampton or the police first, but a Harris County grand jury believed HPD’s version of the story and declined to indict the officers for the shooting death of Hampton. What is known is that Hampton took a bullet to the shoulder and collapsed on Dowling Street, and the People’s Party II and HPD exchanged dozens of rounds.

In the middle of the shootout, Sophia Powell, a woman from the neighborhood, drug Hampton to her car and drove him to Ben Taub, where he died. How a shoulder wound killed Hampton has also been a source of speculation for Houston’s black community. Freeman alleges that the HPD snipers were using “illegal hollow point dumdum bullets.”

After the smoke cleared and the shooting stopped, four other people associated with the People’s Party II lay injured, although none fatally. In the hours following the gun battle, HPD would arrest more than 50 people, on mostly minor charges, from the 10-blocks surrounding the intersection of Dowling and Tuam.

by Alex_Wukman