Tab Hunter Confidential

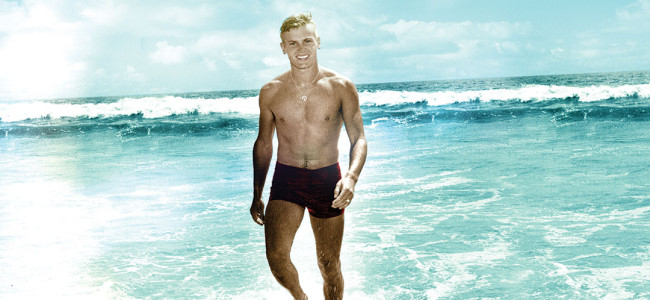

“It’s pretty overwhelming when those things happen,” Tab Hunter tells Free Press Houston in a phone interview. Hunter was a major movie personality in the 1950s even as the studio system that made him a star was imploding.

“You have to accept things as they are, not as you want them to be. That’s one of the many clichés that my mother, a very strict religious German lady, told my brother and myself when we were growing up,” says Hunter.

Hunter had a contract with Warner Brothers and as such was groomed for projects like Damn Yankees! (1958). “Jimmy [Dean] had a picture deal with Warner Brothers but Natalie [Wood] and I were under contract. It was sort of the end of the days for the studio era. Studios were changing drastically, live television, variety shows were coming in, European films, the independents were coming in. The studios had to rid themselves of all their theater chains, so they were in a terrible position. They didn’t know which way to go. We were fortunate to be a part of the end of that era.

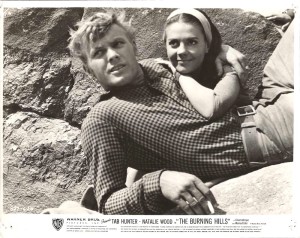

“Natalie and I were in Chicago on tour for a film called The Burning Hills [1956]. When I was there a big disc jockey named Howard Miller heard me singing. Miller put me in touch with Randy Wood of Dot Records,” says Hunter.

Wood met Hunter and recorded him singing “Young Love,” which was also a hit for Sonny James in 1957. Hunter’s version raced to the number one song in the country. “When I heard it driving on Sunset Boulevard four days later I nearly crashed into a palm tree,” says Hunter.

Backing up Hunter on the record were The Jordanaires and Hunter’s hit single knocked Elvis out of the number one slot. “Elvis was not too happy about that.”

Hunter recorded enough material for Dot to release an album but Jack Warner put the kibosh on that prospect. “Warner called me in his office. He said ‘you blankety blank, we own you for everything,’” recalls Hunter. “I said Mr. Warner you don’t have a recoding company. He said ‘well we do now.’ And he started Warner Brothers Records. When you’re under contract you’re under contract. They could loan you out to Columbia or Paramount for quite a bit of money and continue to pay you your weekly salary.

“The studios were falling apart so they would loan you out. I did Dinah Shore, Perry Como, Jimmy Durante or talk shows. They would have me promoting a film they had even if I wasn’t in it. I toured the country promoting The Spirit of St. Louis and everyone knew the plane landed safely at Le Bourget.”

Studio moguls and agents were a force to be reckoned with at the time Hunter’s star was on the rise. The magazine Confidential had planned a story for a September 1955 issue about Rock Hudson. That story was pulled at the request of Hudson’s agent, who was also Hunter’s agent. In effect Hunter was thrown under the wheels of the publicity machinery.

“It was a party I walked into, it got raided. There were men dancing and women dancing, and I was only 17 years old. They never report the actual event, they put their spin on it if you know what I mean,” Hunter says. “I was with Henry Willson. My good friend Dick Clayton wasn’t an agent at the time. He introduced me to Henry who became my agent. When Clayton wanted to become an agent I became his first client. When I left Henry to go to Dick Clayton it was family for God’s sake. I was so worried when that article came out. What’s going to happen to my career? But within two weeks I’d won the Audience Award as the Most Popular Newcomer.”

The list of directors Hunter worked with reads like a who’s who of great helmers from the silent era on through more modern cult directors like John Waters.

On William Wellman: “Bill Wellman was just one of the best directors. He was an incredible director.” Hunter worked with Wellman on Track of the Cat (1954) alongside Robert Mitchum. “Mitchum was great, what you see is always what you got. He could look at a page of dialogue and be ready to shoot.”

Hunter also starred in Wellman’s Lafayette Escadrille (1958), which was held back for a couple of years so that it’s release would coincide with the formation of Warner Brothers Records. “There was a sneak preview and these fans of mine in Pasadena ran up to Wellman and Warner and said you killed Tab Hunter and they were furious.

“I was in Europe and they called me to come back and shoot a new ending. Wellman was not happy with the way Lafayette Escadrille turned out. It was his story about being in the Lafayette Flying Corp during WWI. It was a very colorful story and Warners didn’t want an unhappy ending to the film,” says Hunter.

“Wellman knew exactly what he wanted. There are some really fine directors out there and for every good one there are a lot that I call traffic cops. I put Wellman up there with some of the really great directors I worked with including Sidney Lumet and John Frankenheimer, Arthur Penn. Those directors that came out of live t.v., they knew what they were doing, those guys were not traffic cops”

Hunter also recalled Raoul Walsh. “Ol’ Blood and Guts Walsh is what we called him. He’d been around since the silent film era where he was an actor and director. He was old school, he would actually talk at you while you were doing a scene,” Hunter says.

“Phil Karlson was also terrific,” says Hunter about the 1958 western Gunman’s Walk. “He was all work, but it was all easy and subtle. Of course when you’re working with Van Heflin you’re working with one of the best.”

Eventually Hunter bought his way out of his Warner Brother’s contract, and continued making films both great and not so great in the 1960s. For instance about Ride the Wild Surf (1964) Hunter says, “It was called I need a job. There were a lot of young kids who weren’t serious about their work.”

About Vincent Price whom Hunter worked with on War Gods of the Deep also titled City in the Sea (1965), Hunter remarks: “They used to call him the Merchant of Menace. We talked cooking and he also was a great art collector.”

About the classic black comedy The Loved One (1965): “It had so many off-beat characters like Rod Steiger playing Mr. Joyboy or Liberace playing a coffin salesman. There were some very interesting choices that Tony Richardson made for that film. I like Tony but he was very quirky, he was very strange. I later worked with him on Broadway along with Tallulah Bankhead in the Tennessee Williams’ play The Milk Train Doesn’t Stop Here Anymore.”

Hunter journeyed from the stage and back to the big screen over the following decades. “I was closing a play in Indianapolis when John Waters called me and said ‘I don’t know if you know who I am.’ I said what do you mean, I’m a major fan.” Waters asked Hunter: “How would you feel about kissing a 350-pound transvestite? I replied I’m sure I’ve kissed a lot worse,” says Hunter. The movie was Waters’ 1981 Polyester, complete with scratch and sniff cards handed out to audiences. “I had met Divine years before at the home of David Hockney. John is such a real person, you’d do anything for him.”

Hunter also made Lust in the Dust (1985) with Divine, a camp western directed by Paul Bartel. Hunter produced Lust in the Dust with his production partner Allan Glaser. Glaser and Hunter will be in Houston this weekend promoting the documentary Tab Hunter Confidential, which unwinds as part of the QFest Film Festival.

Tab Hunter Confidential, unwinding Sunday, July 26 at 5 pm. at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, from the autobiography of the same name, tells Hunter’s story in no uncertain terms. Hunter was closeted during the straight ‘50s, yet had an affair with Anthony Perkins another rising star at the time. The relation splintered when Perkins got Paramount to buy the rights to Fear Strikes Out, the tale of a mentally unstable baseball player, as a personal vehicle. Hunter had played the role in a 1955 episode of the anthology television drama Climax!

Tab Hunter Confidential moves with alacrity as the assembled movie clips and talking head interviews (Clint Eastwood, Hunter, others involved with the scene) give the documentary an immediate look of self-recognition. That Hunter can be so composed and yet so willing to set the record straight speaks volumes for the credibility of the story being told.

Hunter mentions that the last time he was in Houston, he and Glaser had come to visit Gene Tierney. “Allan and I visited her in Houston to get the rights for her life story. I’ll never forget her sitting on the sofa. I couldn’t take my eyes off her because right above her was the portrait from Laura.”

— Michael Bergeron